Bartók & Ravel

Full programme

- Ravel, Mother Goose: Complete Ballet (28mins)

- Ravel, Rapsodie Espagnole (15mins)

- Liszt, Piano Concerto No.1 (21mins)

- Bartók, The Miraculous Mandarin Suite (21mins)

Performers

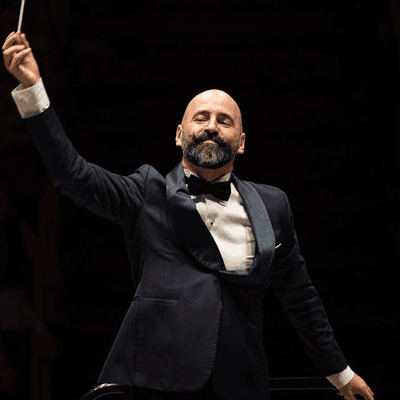

Pierre Bleuse

Conductor

Ryan Wang

Piano

Introduction

I am so excited for my debut performance with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra. I have only heard amazing things about the orchestra from friends who have enjoyed playing with them and I’m particularly excited to be performing the Liszt.

Liszt is one of my favourite composers. His first piano concerto is full of virtuosity whilst being such elegant, charming music. I have been working on the piece quite a lot recently, having only performed it in Bristol a few weeks back too, and I have really come to cherish playing it.

I first heard the piece when I was very young as we owned a CD of Krystian Zimerman playing all of Liszt’s piano concertos and so I would often hear the piece played in the car whilst growing up.

My favourite moment in the concerto is in the third movement. The piano part has a very charming, almost sparkling melodic line in the upper register and alongside it there is the most fantastic dialogue with the triangle. Whenever I play that part of the piece it makes me smile.

The concerto as a whole acts like one whole movement, divided into four parts. It opens with a grand beginning, settles down in the second movement and then comes to life again. There’s a dramatic theme that reoccurs throughout the whole work and so the piece lends itself naturally as an extremely narrative work, taking the player and listener on a journey.

Not only will it be my debut with the orchestra, but also with Pierre Bleuse and I am really looking forward to working together. I’d like to thank the CBSO for making this opportunity possible for me, I really am very excited to play with you all.

Ryan Wang

Piano

Programme Notes

Enter a world of rhapsodies and magical tales – some of them darker than others. Led by French conductor Pierre Bleuse, the CBSO performs two of Ravel’s most beautiful orchestral works: a suite of fairy tales and a sensuous, shimmering evocation of Spain. You can almost feel the heat rising off the pages of the score. On the darker side of the tracks we find Bartók’s Miraculous Mandarin in an urban tale of savagery; its score is both earthy and visceral. By further contrast, BBC Young Musician winner 2024 Ryan Wang is the soloist for Liszt’s vibrant, romantic first piano concerto, full of passion, fire and wistful memories.

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937)

Mother Goose Suite

Ravel’s Mother Goose (in French, Ma mère l’Oye) began life as a suite for piano duet composed in 1910, comprising a series of delicately evoked fairy-tales. The following year Ravel was approached by the director of the Théâtre des Arts, Jacques Rouché, to devise a ballet scenario based on the suite. Ravel came up with a beguiling ‘Sleeping Beauty’ narrative: Princess Florine accidentally pricks her finger and falls asleep for 100 years. In time-honoured fashion, a Bad Fairy wishes Florine to die; a Good Fairy instead provides the sleeping Princess with a series of dreams to while away the century.

The five movements from the original suite are supplemented by a prelude, some brief interludes (where Ravel goes to town with some delicious orchestral effects), and a vivacious ‘dance of the spinning wheel’. The Prelude eases the listener into a sumptuous, magical world – soft, slow-moving chords, gentle, summoning fanfares in the horns, then bird-like woodwind followed by a mysterious orchestral ‘swirl’. Florine’s dreams then begin. ‘Pavane au belle au bois dormant’ (Sleeping Beauty), is wistful but with a stately, dance-like quality. ‘Petit Poucet’ (Tom Thumb) is on a melancholy journey in the second movement, encountering further birdsong on the way. Only at the end – as fellow composer Messiaen puts it – does a ’major third at last [put] a smile on Tom’s face.’ Beauty and the Beast engage in a waltz-like dialogue, the themes of each heard individually at first, then gradually forming a tender partnership by the end. ‘Laideronette’ is more virtuosic, with some evocative, gamelan-inspired passages. The final movement (‘Le jardin féerique’, or fairy garden) sees Princess Florine’s dreams interrupted by Prince Charming. It is largely in a restrained C major, quiet for the most part until a wonderfully-sustained build to the final, spine-tingling bars.

Rapsodie Espagnole

Ravel composed Rapsodie Espagnole shortly after his Spanish-set opera L’heure espagnole, a farce involving multiple adulteries and shenanigans inside grandfather clocks, yet set to the most beguilingly drowsy music. These are just two among the other Spanish-themed works in Ravel’s catalogue, including Alborada des Gracioso and a habañera-like Vocalise While other composers flirted with an ‘espagnole’ style, Ravel’s was perhaps more deeply felt, in part because of his Basque heritage; indeed, the Spanish composer Manuel de Falla noted a ‘subtly genuine Spanishness’ in Rapsodie Espagnole.

The Rapsodie opens unobtrusively, sidling into our awareness with a soft falling melody (which recurs elsewhere in the work). The opening music is sensuous and sleepy, as if barely able to move on a warm evening. It briefly rouses itself for a gorgeous shimmer in the strings, and later a brief show-off for woodwind, before reclining back into the falling melody. ‘Malagueña’ is more energetic with its dancing rhythms and joyful bursts from the brass and percussion, though the return of the falling figure keeps the tempo under control. The third movement is a ‘Habañera’ (another dance form), based on a gently swaying piano piece from some years earlier which Ravel subjects to some stylish orchestration, including playful slides in the strings. In ‘Feria’, Ravel finally lets rip with the full ensemble in a movement bristling with energy and fire. It subsides briefly into a languorous central section, a delicious musical ‘yawn’ intermingling with the opening falling melody. The bustle of the opening returns, gathering so much in momentum it threatens to fall into chaos – but saves itself with the utter exuberance of the final bars.

Franz Liszt (1811-1886)

Piano Concerto No.1

Given Liszt was such a famous pianist, it seems surprising that he waited until he had more or less retired from the concert platform to compose his first Piano Concerto. However, not only was it not quite his first concerto – there were several earlier works, now lost – but it took him over 20 years to arrive at a version he was happy with. He began the concerto in the early 1830s, and produced a first draft in 1835, yet at around the same time he had to go into semi-exile as a result of his relationship with the married Marie D’Agoult with whom he would have three children. As his relationship with Marie began to deteriorate later in the decade, he began to return to the concert platform – and in a big way. ‘Lisztomania’ ensued and lasted some eight years: performances to crowds of thousands, piano ‘duels’ with rival performers, and delirious responses from crowds of fans, some of whom would scramble to retrieve his cigar butts as souvenirs.

Despite these dramas, he had not forgotten his concerto. He prepared a radically rewritten version in 1839, then revisited it again in the late 1840s, worrying at it until he was finally satisfied, and giving the premiere in 1855. The result is a brilliantly expressive, concise – in some performances less than 20 minutes in duration – and tightly-constructed work, more like a symphony in its thematic consistency across the movements. Though full of technical challenges and sparkling passages of play for the soloist, it is far from an ‘empty’ display of virtuosity. Yet Liszt was nervous that this work, so long in gestation, would baffle its audiences; the conductor Hans von Bülow supposedly remarked that the opening phrase could set the words ‘“Das versteht ihr alle nicht, haha!” (“You do not understand any of this, haha!”). Critics of early performances were not altogether impressed, but it has since become one of the most well-known and loved concertos of the Romantic period.

This ‘Das versteht’ statement gets the proceedings off to an assertive start, and the concerto as a whole overflows with confidence, and rich, melodic invention. Even in the opening movement there is a passage of melting lyricism amidst its otherwise stormy nature, and the Adagio sings a melody of ravishing beauty. As this movement melts away, a triangle playfully heralds the next, and continues to duet skittishly with the soloist. (The orchestration throughout this section is as light as a feather, somewhat resembling one of Tchaikovsky’s ballet scores.) The ‘Das versteht’ motif returns to round off the movement, before reprising the melody of the Adagio as a spirited march. Further themes from earlier in the concerto gather and mingle across this energetic finale, democratically distributed across soloist, ensemble, and some characterful solos for wind and brass instruments. The movement concludes with a rousing, major-key celebration of the opening motif, the final bars of which seem to have anticipatory applause built into them.

Béla Bartók (1881-1945)

The Miraculous Mandarin Suite

Bartók’s ‘pantomime ballet’ The Miraculous Mandarin’, completed in 1924, is a blistering tale of violence and sexual exploitation, as well as a portrayal of racism and the consequences of poverty. The music is correspondingly visceral, hurling the listener into what Bartók called ‘hellish music…horrible pandemonium, din, racket and hooting’ at the start: shrieking winds, scrambling strings, and trombone blasts resembling car horns. It is like being plunged immediately into the final, blood-curdling moments of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, yet transported to a dingy back alley. The ‘sacrificial maiden’ here is a young woman, forced by three thugs into seducing customers off the street. Her three sinuous seductions are, as Stephen Downes has noted, played out over a low, rumbling chord – a reminder that ‘the city never sleeps’. Her third attempt is for a mandarin, a Chinese official, who scares her by lunging for her, then is pursued around the room by the thugs. The suite ends at this point in the narrative (in the ballet, the mandarin defies three murder attempts before finally succumbing to an embrace from the young woman – and bleeding to death). Even without this violent ending, the suite captures with white-hot intensity Bartók’s ‘hellish’, uncompromising portrait of urban savagery.

© Lucy Walker

Featured image © Andrew Fox