Kazuki & the Jussen Brothers

Full programme

- Prokofiev, Symphony No.1 (Classical) (15mins)

- Poulenc, Concerto for Two Pianos (19mins)

- Fazil Say, Night (10mins)

- Schubert, Symphony No.9 (50mins)

Performers

Kazuki Yamada

Conductor

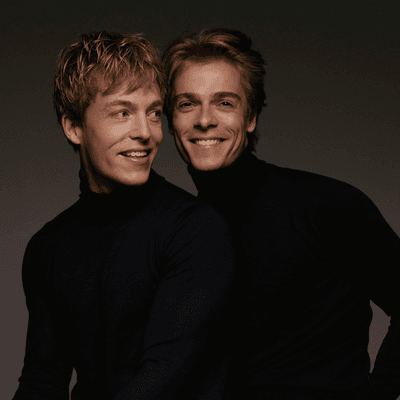

Lucas & Arthur Jussen

Piano

Introduction

To us, Poulenc’s Double Piano Concerto is one of the big highlights of the double repertoires, especially when it comes to orchestral works.

Poulenc was an extremely extravagant person, whether that be in the way he dressed or the perfume he would wear and he shows that extravagance in this piece too. It has a lot of expression and flamboyance - there are so many mixes of styles that it is never boring to play.

Poulenc takes a lot of inspiration from other composers and puts it into his own music, yet the funny thing is, in the end, the music always sounds like Poulenc. The best example of this is the second movement. It starts with music that could easily be mistaken for a Mozart concerto but after a few bars you hear a chord that brings us back in the style of Poulenc immediately.

We think Poulenc is genius for it; for the audience, the music is never boring because before you know it, the change of style occurs and you’re transported into a new world. This concerto in particular has so many realms to relish in, there is such a collage of different atmospheres.

One of our favourite moments that exemplifies this is in the first movement. We have two to three minutes of really virtuosic music and then there’s a big bang and suddenly you end up in what we imagine as a pure French Parisian café, a little bit blurry from the smoke of cigarettes.

Above all, what Poulenc does best is create great dialogue between the orchestra and the pianos. We especially have a lot of interaction with the percussion – look out for it, visually it's quite the treat as you can see just how much is going on.

We’re always happy to play this double concerto, especially with this fantastic orchestra. Kazuki Yamada is someone we admire – for us, he is one of the greats of this moment and we feel very privileged to be back playing in this fantastic hall. It’s a gem of a concerto and we hope you enjoy it.

Lucas & Arthur Jussen

Piano

Programme Notes

‘Life in every fibre, colour in the finest shadings, meaning everywhere’. So wrote Schumann on Schubert’s final symphony, aptly subtitled ‘Great’. You are duly invited to experience life, colour and meaning across the whole of this exhilarating programme, led by Kazuki Yamada and showcasing the exceptional Jussen Brothers on the piano. Prokofiev pays homage to the classical era in his First Symphony, while Poulenc channels both Mozart and gamelan music in his brilliantly playful double concerto. Fazıl Say’s ‘Night’ is a funky, fast and furious work, especially composed for the Jussen Brothers.

Symphony No.1 (Classical)

Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953)

Prokofiev’s ‘Classical’ Symphony is one of his most well-known and easy-to-love pieces, intended by the composer to be both pleasure and provocation. At the time of its composition in 1916-7 Prokofiev was known for his experimental and spiky style (the snarly dissonances of his second Piano Concerto in 1913 led critics to believe he had gone mad). The Symphony no. 1, by contrast, is an elegant tribute to the orchestral style of Mozart and Haydn with only occasional flashes of modernity. It was written, extraordinarily enough, during the Russian Revolution of 1917, though not in the midst of gunfire but in the countryside outside Petrograd (Prokofiev had been exempted from military service). In his diary, Prokofiev imagined the reactions from his former professors to his ‘insolence’ in evoking Mozart: ‘look how he will not let even Mozart lie quiet in his grave but must come prodding at him with his grubby hands, contaminating the pure classical pearls with horrible, Prokofievish dissonances’.

While those comments contain Prokofiev’s trademark snark, the Symphony is sweetness itself. The opening movement bubbles with irrepressible high spirits, the ‘Larghetto’ is a charming, gently pulsing waltz, while the Gavotte has a deliberately off-kilter quality, lurching from one end of the scale to the other. In the finale, even Prokofiev thought he might have gone too far with what he described as its ‘indecent’ levels of good humour – yet at the same time confessed ‘I was hugging myself with delight all the time I was composing it!’. In turbulent times, then and now, this sunny Symphony is an absolute tonic.

Concerto for Two Pianos

Francis Poulenc (1899-1963)

Poulenc was a self-confessed ‘eclectic’, hoovering up influences from a wide range of figures, including Monteverdi, Stravinsky and Edith Piaf. In his Concerto for Two Pianos (composed in 1932) he absorbs Mozart, music-hall and Balinese gamelan into his own unique combination of heart-stopping melodies and frenzied agitation. This lends this piece – and his music in general – a bracingly modern ‘montage’ style as well as a certain nervous energy. Rather than developing one or two themes and motifs into a large-scale structures he tended to fling several down next to each other, glorying in their strange juxtapositions.

As a case in point, the first movement of the Concerto opens with a brief gamelan imitation (Poulenc had heard the instrument at an exhibition the previous year) before launching into a minor-key caper, followed by a series of thwacks from the drums and discordant fistfuls of notes from the soloists. The music then U-turns into a sumptuous and melancholy passage for pianos over slithering woodwind figures, in turn interrupted by the mood of the beginning. The movement concludes, after a lengthy pause, with an extended, atmospheric tribute to the gamelan, which blends miraculously with the melancholy theme.

The second movement features what Albert Hickling called ‘the great Mozart robbery’; but as Poulenc put it, ‘If the movement begins alla Mozart, it quickly veers at the entrance of the second piano toward a style that was standard for me at that time’. It certainly does: Poulenc soon treats us to one of his most melting, sighing melodies, which intervenes between the various Mozart ‘thefts’. The crowd-pleasing finale finds the mood swinging abruptly between furious displays of technique, nods to the music-hall, heckles from the orchestra, and the ‘melting’ style of earlier. The concerto closes with more gamelan, a cackling descent from the pianists, and a single chord from the ensemble: playful and surprising to the end.

Night

Fazil Say (b. 1970)

There are countless pieces on the subject of ‘night’, many of them for piano (Beethoven’s ‘Moonlight’ Sonata, for example, or Chopin’s many nocturnes). ‘Nocturnal’ music can lend itself to the peaceful, or to the magical (think Midsummer Night’s Dream), or to the uncanny – or, as in Say’s Night - the downright sinister. Composed especially for Lucas and Arthur Jussen, Night conjures up sirens, rumbles, and things that go ‘bump’. The two opening motifs pass between the four hands, one grumbling at the bottom of the keyboard, the other riffing on an eerie melody with a constant trip in its step. In between, the players reach inside the body of the piano to dampen its strings (the ‘secondo’ player’s left arm is wedged there for most of the central, more contemplative section). There is even a certain aggression to the distribution of hands, constantly overlapping and threatening to crash into each other. This is a fast, funky, and slightly frightening evocation of night: a fever-dream, bordering on a nightmare.

Symphony No.9

Franz Schubert (1797-1828)

Schubert’s ‘Great’ Symphony has an unusually complex backstory, including a starry cast of characters, confusion over its date, and a classic ‘discovery’ after death. It is also one of those works which caused musicians at early performances to scratch their heads in bafflement, and even snort with laughter. For many years after his death, it was believed Schubert had been wrestling with the ‘Great’ during his final illness in 1828. The Symphony had in fact been written in 1825 and completed in 1826 when the composer was in relatively high spirits, following public acclaim for his music and, for once, a steady income from publications. On finishing the ‘Great’ Symphony Schubert also ended a run of unachieved or incomplete symphonies (including the famously ‘Unfinished’ no. 8 of 1822). No. 9 was, however, rejected for performance. The Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde (Society of Friends of Music) in Vienna gave it a run-through but thought it far too long and complex for a public airing.

It had to wait until Schumann visited Schubert’s brother ten years after Schubert’s death, and was astonished to be handed the manuscript of such a substantial, unperformed work. He sent it to Mendelssohn, who conducted the first performance of the Symphony in Leipzig in March 1839. Schumann, in a typically ardent letter to his future wife Clara, wrote that on hearing it he had been: "transported…the instruments, they are human voices, and spirited beyond measure… and this length, this heavenly length like a novel in four volumes… I was completely happy, and wished for nothing else save that you might be my wife and I could also write such symphonies."

The ’heavenly length’ of the Symphony makes it easy to understand the ‘Great’ subtitle, though that was originally used to differentiate it from Schubert’s other, shorter, symphony in C major (no. 6). But it has an undeniably monumental quality, suggesting a flexing of muscles in the year after Beethoven’s own mighty 9th, the premiere of which Schubert had attended in 1824. (There is a brief reference to Beethoven’s ‘Ode to Joy’ in the finale.) Schubert’s ‘Great’ is ambitious in scale, and decidedly unconventional with its bouts of obsessive repetition and its barely-controlled rhythmic exhilaration.

Each movement is an impressively expansive statement of its own. The punchy assertiveness, at times aggressiveness, of the first movement stems from the rhythm of the opening horn melody, and the forceful use of trombones (quite unusual for the time). The second movement is at least as long as the first, showing off Schubert’s remarkable skill at melody – the opening oboe solo is sublime. Yet it defies serenity, partly through its chugging minor key, and definitely with its shocking blast of brass in the middle section. The Scherzo, with an atmosphere of perpetual motion, gives a taste of the wild energy of the finale. Indeed, we might have some sympathy with the Viennese Gesellschaft, confronted with such manic flurries of triplets. Beethoven’s ‘Ode to Joy’ appears almost insouciantly on the woodwind about five minutes in, casually dropping into the propulsive, rhythmic texture. Anything you can do, Schubert appears to be saying, I can do at least as well, as he drives his symphony towards its boisterously triumphant conclusion.

© Lucy Walker

Featured image © Marco Borggreve