Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No.2

Full programme

- Coleridge-Taylor, Ballade for Orchestra (11mins)

- Rachmaninoff, Piano Concerto No.2 (32mins)

- Wagner (arr. Gourlay), Parsifal Suite (45mins)

Performers

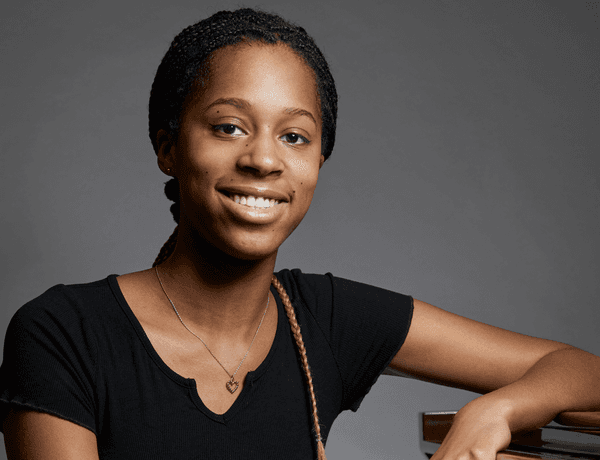

Jeneba Kanneh-Mason

Piano

Andrew Gourlay

Conductor

Introduction

© Andrew Gourlay, Conductor

Bringing Parsifal Suite to the magnificent acoustic of Symphony Hall feels like the climax of what has been a 7-year project.

Back in 2016 I was scratching my head. How could I perform the great orchestral set pieces from Wagner’s opera Parsifal in concert? The opening prelude has been a regular feature of orchestral repertoire for as long as anyone can remember. Often, it’s performed in combination with the Good Friday Music, a pairing that many concert-goers have grown to love.

But what about the rest? The Act 2 Prelude, conjuring up Klingsor’s magical realm, is blisteringly dramatic and offers fast-paced contrast. The Act 3 Prelude is a wonder of the musical world, as are are the mighty centrepieces of the outer acts, the interludes of Transformation Music, which swell our emotions as the opera stage transforms from forest into castle. Both passages are as astonishing as anything I’ve heard on a concert stage. So where’s the catch? It all comes down to Wagner’s gift for steering the audience. Just when the orchestra appears to be reaching a conclusion, the music morphs imperceptibly into the next vocal scene. To stop in concert would be like stopping mid-sentence.

I was determined to avoid composing new endings or interludes in the style of Wagner – better to respect the original. My solution instead was to sit the extracts in an order in which they could run into one another, either directly or in one case with a stitch of Wagner from elsewhere in the opera. The result was unexpected – it just feels right. Having published and recorded Parsifal Suite, I hope that others now have greater access to this extraordinary music. I’m delighted to be with the CBSO for this, the first UK performance since the record release.

Coleridge-Taylor, Ballade for Orchestra

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912)

Coleridge-Taylor was one of those composers – like Britten, like the much earlier Mendelssohn – who started early and had no doubts about their musical destiny. His talent may have come from his musical grandfather – a farrier (or blacksmith) by trade, he also played the violin – and his uncle, who became a professional musician. His family was not well off: he was raised by his mother, Alice, and his grandfather (his father – a doctor from Sierra Leone – had returned to Africa when Alice was pregnant, not knowing of the boy’s existence). The family worked hard to support him in his early lessons and future ambitions. He learned violin with a local teacher in Croydon, then later won a scholarship to the Royal College of Music in his teens, taking composition lessons with Charles Villiers Stanford.

The Ballade for Orchestra is one of his earliest works, written when he was barely out of college. It was commissioned in 1898 by the Three Choirs Festival, who had originally offered the opportunity to Edward Elgar. Elgar instead heartily recommended Coleridge-Taylor with the words ‘I wish, wish, wish you would ask Coleridge-Taylor to do it… he is far and away the cleverest fellow going amongst the young men.’ The Ballade was well-received after its premiere, and a glowing interview in The Musical Times remarked that Coleridge-Teylor was a ‘very gifted musician who has something to say and, moreover, something worth saying.’

The Ballade is a confident, flowing and gorgeously lyrical piece, opening with a theatrical trill followed by two themes: the first in a rocking, rolling style, the second a longer, leaping melody. These two themes chase each other around in the first few minutes, before ushering in a more romantic passage with a soaring melody. The opening themes gallop back, then play out in a variety of styles and inventive orchestrations (at one point, a slinky version of theme 1 sounds like something out of cabaret). We are treated to a longer, even more passionate version of the central theme again before the first two return to close out this exhilarating orchestral work.

Rachmaninoff, Piano Concerto No.2

Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943)

I Moderato

II Adagio Sostenuto

III Allegro Scherzando

The 1946 film Brief Encounter begins with a train roaring out of the fictional Carnforth station. Its thunderous noise obscures the initial opening notes of the film soundtrack; the dramatic start of Rachmaninoff’s second piano concerto, with its spread chords and turbulent melody, emerges from the cacophony. Right from the start, the film conveys a sense of urgency, and of surging passion. It was Noël Coward’s idea to use the Rachmaninoff this way – he wrote the screenplay – and Coward’s biographer Oliver Soden notes that the music gives this British, suburban tale of thwarted love a thrill of Russian melodrama. (Another film, The Seven Year Itch starring Marilyn Monroe, has the deluded hero attempting to seduce Monroe with the same piece; she prefers Chopsticks). All of which preamble is to set the scene for a work which – while some might consider it a cliché – still has an extraordinary dramatic power in performance.

This power is conveyed through the magical way Rachmaninoff writes for piano (a brilliant performer, he was the soloist at the premiere in 1901), but perhaps most through its seemingly endless supply of yearning melodies. The opening theme, for example, lasts an initial eight bars, but then expands into a continuous sequence, eventually lasting some 44 bars. After a fanfare-like

flurry, a new, equally gorgeous theme begins in the piano. And so it continues. The second movement starts with yet another rapturously seamless tune (years later to become the basis of Eric Carmen’s rock ballad ‘All by myself’, made famous in yet another film: Bridget Jones’ Diary). Comprising a dreamy series of triplets, and is deliberately off-kilter with the orchestral theme above. The final movement, in mostly a more jaunty spirit, has another show-stopper as its second major theme.

The Concerto’s melodies are generously shared between orchestra and piano, the soloist often duetting with a member of the woodwind, and for such a virtuosic work for piano, there is surprisingly no lengthy ‘cadenza’ for solo piano. Instead, there are brief sections of fireworks in each movement before the main business of this work – melody – is reclaimed. The Concerto ends in a well-earned major key, all passion finally spent.

Wagner, Parsifal Suite (500)

Richard Wagner (1813-1883)

I Prelude to Act 1

II Good Friday Music (Act 3)

III Transformation Music (Act 3)

IV Prelude to Act 3

V Prelude to Act 2

VI Transformation Music (Act 1)

VII Finale (Act 3)

Wagner’s final opera is one of his longest; and for a Wagner opera, that’s saying something. The original work lasts just over four hours (not including intervals), and is a prime example of how Wagner composes his stageworks in an unbroken, seemingly endless flow, as opposed to breaking down the acts into a series of arias, duets, choruses, etc. Andrew Gourlay’s aim in arranging his suite was to create a substantial orchestral representation of Parsifal that was true to that sense of continuity and seamless blending of scene into scene. The resulting 45-minute work, as he puts it, ‘stitches together’ the opera’s preludes and finale, its ‘Good Friday’ music, and the transformation scenes, where the forest gives way to the Grail palace – a place where, according to one of the characters in the opera, ‘space becomes time.’

Wagner drew on various versions of the ‘holy grail’ legend for his plot, which is a complex one. Putting it as briefly as possible, the story concerns the eternally wounded King of the Grail Knights, Amfortas, who according to prophecy can only be cured by a ‘holy fool,’ a chosen one. Along comes Parsifal, an innocent, and apparently a foolish one. After various trials and tribulations, he comes to realise his status as ‘the chosen one’ and eventually heals Amfortas on Good Friday. Along the way, he reclaims the ‘holy spear’ which wounded Amfortas from the villainous Klingsor, and releases Klingsor’s handmaiden Kundry from a curse.

As with all of Wagner’s operas, principal characters and themes are associated with their own leitmotif, a distinct melody which travels through the opera, transforming over time and in contact with other motifs. The opera – and Gourlay’s suite – begins with the principal motif: a long thread of a tune which gives birth, as it were, to several other motifs and outlines the psychological drama to follow. It starts with a straightforward rising ‘triad’ figure, then becomes more anguished before tailing off ambiguously. It is followed by a suitably noble ‘Grail’ theme, quite similar to the first half of the main motif; and then another associated with ‘Faith,’ again for brass.

As the opera is set in a strange, perpetual cycle, seemingly outside literal time, the music can quite happily reorder itself without losing the psychological sense of the original drama. After the Prelude, Gourlay jumps to Act 3 (the Good Friday music, the ‘transformation’ music, and the Prelude), followed by the preludes to Act 2 and the Act 1 transformation. The suite concludes with the Act 3 Finale. Already in the opening Prelude we can hear the perpetual state of yearning and the eternal suffering of Amfortas. The glorious Good Friday music offers the promise of redemption, while the transformation scenes move in and out of darkness and light – the Act 3 version a reversal of the first. The Act 3 prelude emphasisesthe heaviness and even weariness of the Knights in their perpetual suffering; while the prelude to Act 2 is in the contrasting realm of Klingsor and Kundry, full of malicious energy. The opera ends with the triumphant Act 3 Finale, Amfortas cured, and Parsifal now the King of the Grail Knights. The motifs in the Finale – notably the main theme – are sweeter, less anguished. They finally allow themselves to resolve into peace.

Programme notes © Lucy Walker

Featured image © John Davis