Youth Orchestra: Mahler 5

Full programme

- Honstein, Juvenalia (25mins)

- Mahler, Symphony No.5 (72mins)

Performers

Jac van Steen

Conductor

Jordan Ashman

Percussion

Introduction

A very warm welcome to Birmingham's Symphony Hall this afternoon as the brightest musical talents in the Midlands play epic Mahler.

In many of his letters to his friend, and protégé, Bruno Walter, Mahler reflects on how his music might be received by an audience. It is clear that Mahler was aware of the complex and demanding structures of his symphonic work: "In tantum quantum I can be really satisfied with my work, but I really feel sorry for those who have tolisten to all the sad music I have created...". (Klagenfurt, 20 August 1901)

As he began to compose his Fifth Symphony, Mahler fell in love with "the most beautiful girl in Vienna": Alma Schindler - a young composer who was studying with Alexander Zemlinsky. Gustav hoped that Alma would become Mrs Mahler as soon as possible, so - as an expression of his love - he composed one of the most beautiful pieces of music ever written. This love letter, for strings only, plays a central role in the symphony.

The Adagietto is surrounded by enormously energetic, complex and often surprisingly contradictory sounds, orchestrated for large forces: from one extreme to the other, in short, Mahler in persona, expressing his adventurous life as conductor/composer/lover, trying to fulfil his desires in life. This masterpiece undoubtedly shows his self-confidence, combining trivial aspects with more elevated and traditional elements of music history.

The presentation of this afternoon’s concert comes from the orchestration of this extraordinary symphony, in which Mahler seems to summon the richest possible colours from each voice in the orchestra, with melodic ideas exchanged between musicians as though in conversation. Members of the youth orchestra have identified moments where Mahler most clearly brings their voices to the fore, and we have found ways to make some of these moments visible at the same time as we are hearing them.

We have also followed the emotional journey described in Mahler’s annotations within the score, and those captured in many letters to Bruno Walter and elsewhere:

- A funeral march

- Moving like a storm with enormous force

- Scherzo: a walk in the mountains

- Adagietto: a love letter

- Rondo: The world in perfect balance

The practice of standing in orchestras for moments like this, usually marked “espressivo” was well established in the nineteenth century - and often Mahler marks the points when he wants the horns, oboes, and clarinets to play with their bells up. Mahler was very used to audiences clapping, cheering, and sometimes hissing between movements. All the rules we now associate with classical music were invented after this symphony was composed - so for this piece, please feel free to clap whenever you like.

Jac van Steen, Conductor

Tom Morris, Theatre Director in Residence

Programme Notes

A song of love, struggle and delirious joy... there’s a lifetime of emotion in Mahler’s tremendous Fifth Symphony. The superb young musicians of the CBSO Youth Orchestra never hold back, and today they’ll go straight to its deeply romantic heart. First, though, a shot of neat inspiration as BBC Young Musician 2022 winner Jordan Ashman conjures sounds from beyond the imagination in Robert Honstein’s extraordinary percussion concerto.

Juvenalia

- Brash and raucous

- Contemplative

- With abandon

“Waves of colourful sounds” was how the New York Times described the music of Robert Honstein, an American composer who says that he comes from “Boston, by way of New Jersey, Connecticut, Texas, and New York City.” A self-confessed musical omnivore with an irreverent sense of humour, Honstein has written chamber, vocal and orchestral music, with a particular passion for percussion. “I frequently make up elaborate contexts for my music - back story, narrative, images”, he says. “I love the abstraction of music and how it can become a metaphor for an infinite possibility of ideas”. Concerning Juvenalia, the percussion concerto that he wrote for Colin Currie in 2019, he says:

“In Ancient Rome, Juvenalia were coming of age festivals featuring games, theatre and ritual celebrations. Ironically, these events were noted for the childish behaviour of their participants, youth and elders alike. Accounts from the time suggest wild, debaucherous display was not only encouraged but required. Anyone not acting sufficiently irreverent risked expulsion or worse.

In my concerto, Juvenalia, I seized on this idea of youthful carousing. At the same time, I considered the linguistically similar notion of juvenilia. Sometimes disowned, often discarded, these early works are at best a footnote to otherwise noteworthy catalogues. Yet these raw, unpolished efforts contain portentous kernels: seemingly insignificant ideas that may grow in surprising, beautiful ways. Looking back at my own early compositional efforts, I’m convinced there are connections between my youthful creations and the music I write today. As I grow older, I listen to these first attempts and think perhaps there’s more to discover. Maybe these capricious, unrefined pieces hold secrets yet to be revealed.

Tapping into both the wild energy of Juvenalia and the elusive premonitions of juvenilia, the concerto begins with music reminiscent of my high school garage band. Playing a modified drum kit, the soloist careens through a series of loud, bombastic episodes, overflowing with youthful energy and wild abandon. The second movement takes a step back. Moving from kit to vibraphone, the soloist leads the orchestra on a slow and spacious soliloquy. Lyrical and contemplative, the music evokes a restrained, classical sensibility. Finally, the third movement revisits the frenzied exuberance of the opening, but now with even greater urgency. A reckless, unrelenting momentum pushes the music forward as the soloist unleashes a torrent of semiquavers in a furious drive to the finish.“

Symphony No. 5

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

I.Trauermarsch.

Stürmisch bewegt, mit größter Vehemenz

II. Scherzo.

III. Adagietto - Rondo-Finale

The hut in the woods

The village of Maiernigg in the Austrian province of Carinthia lies beneath wooded hills, on the shores of Lake Worthersee. In 1900 Gustav Mahler – music director, since 1897, of the Vienna Court Opera – built himself a lakeside villa. It was a place to spend summers; somewhere that he could swim, hike and study scores. And he arranged for the construction of a tiny single-room “composing cottage”, buried in the forest above the lake. “The summer was lovely” he later recalled, and deep in the woods in his newly-built retreat, he completed his Fourth Symphony. The next summer, he wrote a series of songs. And some time before 5th August 1901 he told his friend Natalie Bauer-Lechner that he was working on a new symphony, his fifth.

Back in Vienna, on 7th November 1901 he met the 22-year old Alma Schindler at a dinner party. (Gustav Klimt was among the guests) They disagreed over the music of Alma’s teacher Alexander von Zemlinsky, and sparks flew. “He studied me long and searchingly through his spectacles” she remembered, and they agreed to meet again the following day. They became engaged, in secret, on 7th December 1901, and were married on 9th March 1902.

That summer, Gustav took Alma to Maiernigg –“ a life of utter peace and concentration”, she recalled. He resumed work on the new symphony - his first purely orchestral composition since his First Symphony, back in 1889 - and before they left Maiernigg at the end of August, Gustav played Alma the finished score on the piano in his hut. “It was the first time he had ever played a new work to me, and we walked, arm in arm up to his hut with all solemnity”, she remembered, years later. Mahler conducted the world premiere of the Fifth Symphony with the Gürzenich Orchestra in Cologne, on 18th October 1904.

The music

The symphony begins in darkness: with the call of a solitary trumpet. “The first three notes should be played somewhat hurriedly, in the manner of military fanfares”, wrote Mahler, and what follows is a funeral march of the darkest kind. Two interludes break the sombre procession – an anguished outburst, and a quieter, pleading melody for the violins. With a thunder of cellos and basses, the second movement breaks over the scene like a mountain storm. Woodwinds shriek like fleeing birds; but from the tempest, new ideas begin to emerge: a long, yearning string melody (like a memory of the funeral march) and a noble hymn for the brass – the symphony’s first real vision of hope. The storm sweeps back in, and blows itself out with a final, inconclusive thud.

That’s the end of the first part of the symphony. Now, with a sudden horn-call, and a little tingle of joy and light, Mahler changes the scene completely. The symphony’s big, exuberant central Scherzo is also its turning point – part country dance, part rough-cut Viennese waltz, topped by a spirited solo line for the orchestra’s principal horn. Mahler said that this movement was “the tail of the comet” – “humanity in the full brightness of day, at the zenith of life”. At its centre, it slows. The skies darken, and horns and trumpet call to each other as if across vast spaces; at once desolate and heroic.

The third part of the symphony begins with another transformation. Mahler dispenses with everything except strings and harp and withdraws into a breathless and intimate new world. At first the melody of the Adagietto (“little Adagio”) is hesitant; the harp plucks tentatively as a sense of deep peace and then growing passion spreads through the music. It seems almost certain that Gustav wrote this movement after meeting Alma, and the Dutch conductor Willlem Mengelberg – one of Mahler’s most trusted colleagues – said that Mahler had sent the score to Alma, accompanied by the words of a love song:

How much I love you / You, my sun / I cannot find the words to say

Only my longing can I lament to you / And my love, and my delight.

The Adagietto melts into near-silence – or perhaps a place where even music cannot reach. Once again, the horn picks up the thread; the woodwinds respond and the orchestra rolls into a great sunlit Rondo – which finds time along the way to revisit the joys and terrors of the previous movements, to engage in vigorous musical debate, and to give a mischievous twist to the lovely melody of the Adagietto. Finally, amid cascading scales and fanfares, the brass crown the entire symphony with the hymn of triumph that had been glimpsed (and then lost) in the turmoil of the second movement. There’s a final sideslip, and the symphony hurtles to a euphoric close. At the top of the score Mahler wrote the dedication: “To my beloved Alma, the true and courageous companion on all my life’s journeys”. “Because,” writes Mahler’s biographer Constantinos Floros, “he strongly believed he had found the greatest happiness of his life”.

Notes by Richard Bratby

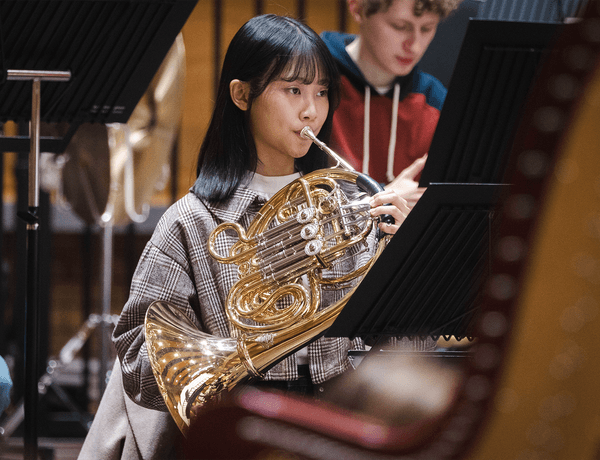

Featured image © Hannah Fathers