Kazuki Conducts Ravel & Poulenc

Full programme

- Ravel, Daphnis et Chloé: Suite No.1 (11mins)

- Ravel, Piano Concerto in G major (23mins)

- Ravel, Daphnis et Chloé: Suite No.2 (16mins)

- Poulenc, Stabat Mater (31mins)

Performers

Kazuki Yamada

Conductor

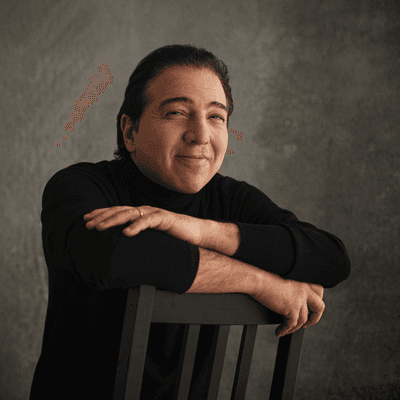

Fazıl Say

Piano

Eleanor Lyons

Soprano

CBSO Chorus

Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra Chorus

Introduction

I am really looking forward to performing alongside the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra in this concert. I will be playing Ravel’s Piano Concerto which is an absolute masterpiece and one of the most important piano concertos of the twentieth century.

I am a huge fan of Ravel’s work and his piano concerto is a very familiar piece of repertoire for me. It appears in my schedule every year, playing it at least one or two times in a season. Despite knowing it very well and performing it often, I always discover new ideas in the music when I revisit it. The concerto evokes new stories and feelings each time I play it – such is the magic of playing music live!

The concerto is most famous for its second movement – it is very deep and slow with reflective melodies and extremely interesting harmonies. Knowing how fantastic this orchestra is, I just know they will bring out all the underlying colours of Ravel’s harmonies with such vibrancy and style. I hope you enjoy this movement as much as I enjoy playing around with its effervescent colours.

I know this orchestra well – I last performed with them in 2023, playing Saint-Saëns’ Piano Concerto No.2. Kazuki and I go back a little further, having first met about twelve years ago in Switzerland. He is such a joyful conductor to work with and I greatly look forward to performing with each other again.

The rest of the programme visits Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloé Suites and Poulenc’s Stabat Mater – what a romantic programme of works, I hope the audience enjoy it. I personally relish in the music of these composers and look forward to sharing some of their music with you.

Fazıl Say

Piano

Programme notes

No-one can make an orchestra shimmer like Ravel – his Daphnis et Chloé could light up a whole town. Meanwhile, he and Fazıl Say strut their stuff like Gershwin in the jazz-inspired Piano Concerto. Eleanor Lyons’ shining soprano is perfect for Poulenc’s gorgeous Stabat Mater.

Daphnis et Chloé: Suite no.1 and No.2

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937)

Paris in the early 1900s was the absolute centre of cultural activity. Composers, artists, choreographers, and designers from all over Europe mingled in the city, and several of them were imaginatively thrown together by the Russian impresario Sergei Diaghilev. His Ballets Russes company was responsible for some of the most extraordinary cultural milestones of the 1910s. One of those was Ravel’s Daphnis and Chloé, choreographed by Michel Fokine (others included Stravinsky’s Petrushka and the The Rite of Spring).

The scenario is based on an ancient Greek story, retold in the 1500s by French writer Jacques Amyot. It is a tale of the goatherd Daphnis and the shepherdess Chloé, who fall in love, are separated via pirate abduction, then reunited through the intervention of the Gods. Fokine and Ravel somehow managed to work out a shared understanding of the story, despite Fokine’s lack of French and Ravel only knowing how to swear in Russian. The two clashed considerably over the style of the ballet, with Fokine drawn to an archaic, stylised form of ‘Greekness’, and Ravel preferring ‘the Greece of my dreams … imagined and painted by the French artists of the 18th century’. The premiere in 1912 was not a huge success, but the music, especially in the form of two extracted suites, has been consistently popular with orchestras and audiences alike.

Suite No.1 drops us into the drama towards the end of Part 1. Daphnis and Chloé have won each others’ attention via a kind of dance-off, but pirates arrive and abduct Chloé. Suite No.1 begins as Daphnis is prostrate on the ground, his sorrow being tended to by nymphs. Shimmering strings and gentle flutes provide the softly nocturnal atmosphere, along with occasional gusts from a wind machine, and the lightest possible touches from the brass. Ravel’s orchestration, always sublime in its detail, is magical here. The second movement of the Suite corresponds to the opening of Part 2, which in the original ballet was performed by a wordless chorus (here by wind and brass). This contemplative mood segues into action at the pirates’ camp. They are dashing agitatedly about, carrying ‘plunder’ from their recent activities. The music here is suitably frantic, the orchestra roused from the languor of the earlier movements. There is a hectic violence to the scoring, with ‘stomping’ figures and noisy interjections from the brass, building to a punchy, powerful conclusion.

The opening of Suite No.2 is one of the most ecstatic passages of orchestral music ever written. In terms of the scenario, we have skipped over the dramatic rescue of Chloé by the god Pan (in memory of his beloved Syrinx). As day breaks the next morning, Daphnis is lying where the nymphs had left him. Bubbling woodwind figures form the background texture, against which – gradually – a solo violin ‘chirrups’ followed by the first appearance of a gorgeous rising theme in the low strings. This soaring theme builds in stature and passion as, gradually, shepherds appear in the distance, Chloé among them. Reunited, Daphnis and Chloé enact the tale of Pan and Syrinx, with Pan represented by a sinuous flute solo. The final ‘danse générale’ begins with a bristle of tambourines and develops into a somewhat challenging five beats to a bar (the dancers supposedly managed to keep time by mentally reciting ‘Ser-ge-Dia-ghi-lev’). The danse ebbs and flows, surging in and out of the full ensemble, before building to a wild, boisterous climax.

Piano Concerto in G Major

In 1928 Ravel had a revelatory visit to the US, where he heard George Gershwin perform at the Cotton Club in Harlem, spending the evening of his 53rd birthday in the company of the American composer. Ravel was surprised that the American musical establishment did not rate jazz and blues as highly as he did; he gave a lecture in April 1928 entitled ‘Take Jazz Seriously!’, and took his own advice by paying a generous tribute to it in his Piano Concerto in G.

The concerto opens with a bang, or rather a slap: an attention-grabbing beat on the whip and tambourine. The piano playfully warms up with some glissandi (rapid runs up and down the keyboard) while several instruments take solo spots in a carnivalesque opening passage. Jazz makes its appearance after less than a minute. The piano sounds like it is improvising, clarinets and muted trumpets are moody and bluesy, and strings are sensuous. There is also a gorgeously lyrical, climbing theme for piano and orchestra, channelling the sound of musical theatre. The movement is brilliantly eclectic, veering from one mode to another, as if someone was twiddling the dial on a radio, passing through a range of music stations.

In a completely different mood, the second movement is serene and luxurious. It is rightly celebrated for its lengthy and sumptuous melody: Ravel wrote later that he ‘worked over it bar by bar! It nearly killed me!’. It is the longest movement of the three, yet the quality of this ‘flowing phrase,’ as Ravel put it, has the effect of filling the time so agreeably that we barely notice. The finale, by contrast, is over in about four minutes. Back in the circus again, the piano has a fiendish time of it, while wind and brass heckle from the sidelines, occasionally brought to attention by the whip. Jazz is lightly present, mainly in its punchy rhythms and impudent chromatic ‘slides’. The Concerto ends with a burst of fireworks from the piano and some emphatic chords from the band.

Stabat Mater

Francis Poulenc (1899-1963)

Many composers – Pergolesi, Rossini, Schubert and Haydn among them - have tackled the Stabat Mater text, which depicts the anguish of Mary at the foot of Jesus’s cross. Each have had their own approach to this powerfully emotional text – Rossini’s, for example, sounds as if it sprang from one of his operas – and Poulenc is no exception. His Catholic faith, reignited after the death of a friend in 1936, was deeply felt and his Stabat Mater was composed in response to another bereavement. His friend, the artist Christian Bérard, had died aged only 46 and while Poulenc briefly considered writing a Requiem, the more personal sense of loss in the Stabat Mater text appeared to resonate more powerfully with him.

The first movement (‘Lacrimosa’) depicts Mary’s weeping. It opens with, and features strongly, the interval of a minor third which in Poulenc’s music is often associated with a state of mourning. The eleven movements which follow are brief – none exceed four minutes – and the second is particularly pithy, brutal in its depiction of ‘bitter anguish’. The third movement, by contrast, bathes Mary’s distress in luxurious harmonies. The Stabat continues, alternating movements which appear to console Mary through a more uplifting mood, or a sensuous sequence of chords, with others which embody her pain (such as IV and V and the later VII and VIII, the former with an incongruous trumpet flourish at the end). The soprano soloist joins at movement VI in one of the most exquisite and touching passages, as Mary regards her dying son. The ninth movement builds to operatic fervour, a foreshadowing of Poulenc’s Catholic opera Dialogues des Carmélites, which he would compose a few years later. The following movement, with its grand writing for strings and soaring soprano is even more in this vein. The dramatic language of no. XI is given a correspondingly fiery treatment, yet is intercut with the softer music from the third movement. The final movement is both a reverential hymn to Mary and a full-blooded surge for the whole ensemble, concluding with a triumphant ‘Amen’.

© Lucy Walker