Shostakovich's Fifth Symphony

Full programme

- Bacewicz, Overture (6mins)

- Sibelius, Violin Concerto (35mins)

- Shostakovich, Symphony No.5 (46mins)

Performers

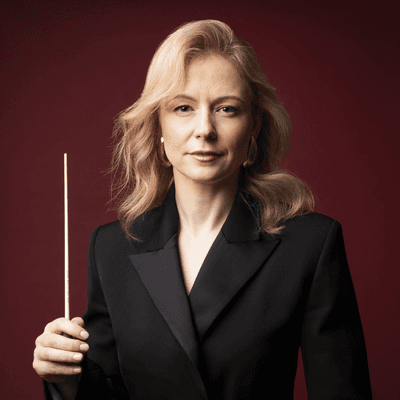

Gemma New

Conductor

Christian Tetzlaff

Violin

Introduction

Welcome! We are thrilled to perform this emotional and dramatic program for you.

Grażyna Bacewicz was a prolific composer and violinist, serving as concertmaster for the Polish Radio Orchestra. Her energetic overture was written during World War II, and it packs a punch with much fanfare and perpetuum mobile.

In Sibelius’ Violin Concerto we appreciate both his deep love for the violin and his genius as an orchestrator. Following the traditions of Tchaikovsky and Mendelssohn, the heartbeat of Finland sings in this rousing masterpiece.

In Shostakovich’s Fifth we experience a journey, from darkness to light. The jagged leaps and falls of the opening passage set a treacherous landscape. Eerie floating threads keep us lost in the fog. I hope you feel enchanted by the l’amour quote from the opera Carmen. It’s like a bird that gives hope, in a world of bleak.

We ramp up the tone with a raucous scherzo that confidently shows off its obnoxious vulgarity. The fragile contrasting theme sounds like a captive ballerina, forced to entertain.

Our third movement moves inward; a requiem for friends who died under Stalin’s orders. From prayer, to nervous shadows, to screaming in terror, then back to a whisper, this string-led movement illustrates the many emotions felt through the Great Purge.

Shostakovich was tasked with the impossible: to compose a work which would satisfy his own artistic principles as well as demands from the Stalinist government. The ending does just that: for some it sounds like triumph, and for others it sounds suffocating.

In today's concert, we hope to give you inspiration and strength through this music, and thank you for experiencing this music with us.

Gemma New

Conductor

Programme notes

Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony, written during the terrors of Stalin’s Russia, sends chills up the spine. Bacewicz’s fizzing Overture was - incredibly - composed during the Nazi occupation of Poland in 1943, while Sibelius’ violinist and orchestra struggle for supremacy against the backdrop of an icy, Finnish winter. Violinist Christian Tetzlaff tackles its monumental solo part, while Gemma New conducts the CBSO in this vital, stirring programme.

Overture

Grażyna Bacewicz (1909-1969)

There is something raw and urgent about Bacewicz’s Overture. It was composed in Warsaw in 1943 during the German occupation in Poland (Bacewicz would flee during an uprising the following year), which perhaps explains its febrile atmosphere. Lasting only six or so minutes, it has the force and emotional impact of a much larger piece, intensified through compression. After an initial timpani rumble the Overture blazes into action, the upper strings in perpetual motion. The rest of the strings soon join in, along with percussive beats from the woodwind, followed by cascades of brass. The frenetic activity continues: even when the full ensemble recedes, the scurrying strings remain. Yet after around 90 seconds the activity gives way for a soft, lyrical passage, resembling a tiny ‘Andante’ movement. The bustling strings and timpani herald a return to the atmosphere of the start, and we’re off again. Against this whirling background Bacewicz introduces theme after theme, any one of which could build towards a mighty conclusion; but time and again she holds the music back, skilfully manipulating the tension. By the end, we are very ready for the final blast of strings and brass.

Violin Concerto

Jean Sibelius (1865-1957)

In the early 1900s Sibelius was in bad shape. He was frequenting drinking establishments in Helsinki, and behaving very badly towards his family and professional colleagues (he promised his Violin Concerto’s premiere and dedication to Willy Burmester, but gave him neither). As a result, his wife and friends staged something of an intervention, arranging for a new family home to be built in the in the middle of the forest at Järvenpää. Sibelius would live there for the rest of his life.

The Violin Concerto, completed in 1904, may have absorbed some of its composer’s turbulent, often quarrelsome nature, along with the dramatic contours of his homeland. It is very much a soloist’s concerto - Sibelius himself was a violinist - yet its extraordinary passages of virtuosity are not for the sake of exhibitionism but rather to participate in a struggle with the orchestra. As violinist Stefan Jackiw puts it ‘there is a craggy cruelty in the orchestral part and in the Finnish landscape…The whole piece is about losing control to nature and just being consumed and devoured by it.’

The first movement is the most complex with the atmosphere of a high-stakes battle. The opening bars suggest an icy, forbidding environment against which the soloist embarks on a long and quizzical passage of play. This opening solo is full of twists and turns, scraps of melody being tested out, then coming to a halt before starting up again. Other instruments gradually join from the sidelines, including woodwind and soft, ominous rumbles from the timpani. After a surprising mini-cadenza from the soloist, silencing the band, the orchestra rejoins for a gloriously romantic sequence. Yet shortly after, the violinist launches into its full cadenza, riffing on themes already heard. Convention has it that the soloist gets a break after this, but the violinist continues to tussle with the orchestra, insistently running through melodies from earlier in the work. The orchestra finally gets a chance to flex its ‘craggy’ muscles before reprising the romantic passage from earlier. However, the final bars find the soloist and ensemble in fiery combat once more, each attempting to dominate the other.

The slow movement is heart-rending, full of long, wistful melodies and sensitive scoring for pairs of woodwind instruments. A passage towards the end, where rising scales in the solo violin are mirrored by falling notes in the flutes and strings, is particularly ravishing. The finale was memorably described by the musicologist Donald Tovey as ‘a polonaise for polar bears’. There is indeed a wrong-footed, occasionally comical side to the boisterous melody (the slightly drunken nature of the opening salvo – with its discordant lurches and tumbles - may have something to do with Helsinki pubs). Later on in the movement the soloist slips and slides on harmonics, high above the rest of the ensemble. The violinist’s recklessly freewheeling style manages – just about – to keep a step ahead of the orchestra. The Concerto ends with a fabulous, bravura display.

Symphony No.5

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony is deeply embedded in its political times. It can even run the risk of being buried under the weight of associations it has carried since its premiere. Briefly, the composer had run afoul of Stalin at the height of the ‘Terror’: ‘disappearances’ of Russian dissidents, and rafts of denunciations by those in fear of their lives. In early 1936 Shostakovich’s music had been ‘denounced’ in a newspaper article if not actually by Stalin then certainly representing his views. Shostakovich was in big trouble, and needed public redemption.

Symphony No.5 was premiered on 21 November 1937 to a rapturous reception, including a half-hour standing ovation at the end and a positive review from Stalin’s Cultural Spokesman, Alexie Tolstoy. Shostakovich was, at least for the time being, safe. However, the Symphony is not a piece of triumphant patriotism, but is rather a work of great contradictions. While supposedly pacifying the powers that be, it simultaneously expressed the pain and terror of the Russian people. At the premiere, audience members wept during the third movement. The finale, ending in an emphatic major key, can seem too triumphant, its final fanfares lasting too long. For the Russian soprano Galina Vishnevskaya the repeated chords at the end were like ‘nails being pounded into one’s brain.’

One of the most striking elements of the score is its transformation of themes. Often, hearing them in their final version at the end of a movement we are moved by their musical journeys. Listen, for example, to how the opening theme – a distinctive, leaping figure – is transfigured from its powerful first appearance at the start, to its shadowy, skeletal form at the end. In between, the epic first movement alternates from fierce, declamatory music to haunting passages of great isolation, even loneliness. The vulnerable exposure of the wind instruments in particular sends a chill down the spine.

Shostakovich was known for displaying dark humour in his Scherzos: the Fifth has one overflowing with punchy melodies, many of them featuring insistently repeated notes (which we shall hear again in the finale). The middle section is a queasy waltz, orchestrated in a variety of ways, as if perceived from multiple angles. After a strange, hushed version of the opening theme on plucked strings, the movement ends boisterously, yet with a somewhat sinister edge.

It is easy to understand the audience’s tears on the first hearing of the slow movement. The winds, strings and celeste share the musical material (brass and most of the percussion are silent), which starts with a long-breathed, solemn melody. As in the first movement passages of surging power alternate with vulnerable, exposed solos. At carefully judged moments the ensemble combines. This is music which appears to recognise individual suffering as well as a collective grief.

The brass and percussion rush to begin the Finale as if bursting to speak, and they play a prominent role throughout: strident trumpet solos, richly clustered horns and military-style drums. Opening with a wonderfully noble horn solo, the central section is quieter, resembling the suspenseful passages of the first movement. The closing section comprises a dramatic build-up to the final chords. The listener can either interpret the closing statement as ‘the tragically tense impulses of the earlier movements … resolved in optimism and the joy of living’ as Shostakovich said, perhaps sensibly, at the time of the premiere; or as ‘nails… into one’s brain.’ Whichever the case, by the end of this remarkable work both music and audience have gone through a transformative experience.

© Lucy Walker

Featured image © Andrew Fox